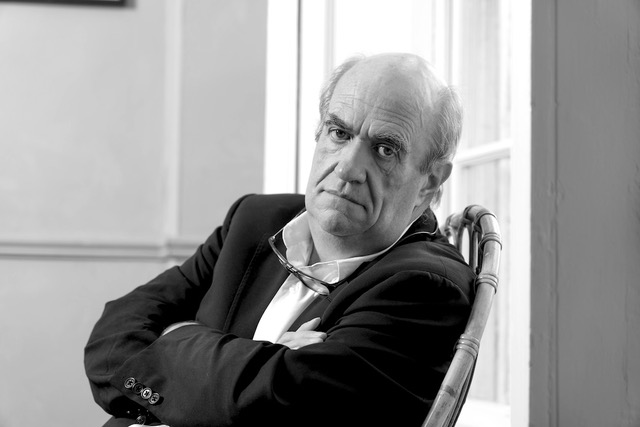

Colm Tóibín è nato in Irlanda nel 1955. È autore di undici romanzi, inclusi Brooklyn e Il mago, e di due raccolte di racconti. La sua opera è stata tradotta in più di trenta lingue.

Giorgia Sensi è traduttrice freelance dall’inglese di fiction, non-fiction e soprattutto poesia. Ha tradotto raccolte di Carol Ann Duffy, Jackie Kay, Gillian Clarke, Margaret Atwood, Eavan Boland, Kate Clanchy, Patrick McGuinness, Kathleen Jamie, Vicki Feaver, John Barnie, Philip Morre, Raymond Antrobus, H. D., Ilya Kaminsky, Mary Jean Chan, George Mackay Brown, e altri ancora, e curato diverse antologie. Tra le sue traduzioni e curatele di poesia si segnalano nel 2020: Le colombe di Damasco, poesie da una scuola inglese, antologia a cura di Kate Clanchy, LietoColle Editore, e The Perseverance di Raymond Antrobus, prefazione di Kate Clanchy, postfazione di Anna Maria Farabbi, LietoColle Editore. Nel 2021: Repubblica sorda (Deaf Republic) di Ilya Kaminsky, La nave di Teseo Editore; H. D. Poesie imagiste di Hilda Doolittle, Interno Poesia Editore. Nel 2022, La fanciulla senza mani e altre poesie, Vicki Feaver, Interno Poesia Editore. Le storiche, Eavan Boland (The Historians), Le Lettere Editore (con Andrea Sirotti). Nel 2023: Danzare a Odessa (Dancing in Odessa) di Ilya Kaminsky, La nave di Teseo Editore. Flèche, di Mary Jean Chan, Interno Poesia Editore; Incidere le Rune, poesie scelte, di George MacKay Brown, Interno Poesia Editore. Con La casa sull’albero, poesie scelte di Kathleen Jamie, Ladolfi Editore, 2016, ha vinto il Premio Marazza 2017 per la traduzione poetica. Ha inoltre ricevuto il Premio Nazionale per la Traduzione 2019, conferito dal Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali (MIBACT).

* * *

* * *

September

The first September of the pandemic,

The sky’s a watercolour, white and grey,

And Pembroke Street is empty, and so is

Leeson Street. This is the time after time,

What the world will look like when the world

Is over, when people have been ushered into

Seats reserved for them in the luminous

Heavens.

Moving towards the corner of

Upper Pembroke Street and Leeson Street,

An elderly man wears a mask; his walk is

Sprightly, his movements brisk. I catch

His watery eye for a watery moment.

Without stopping, all matter-of-fact,

He says: ‘Someone told me you were dead.’

Settembre

Il primo settembre di pandemia

il cielo è un acquerello, bianco e grigio,

Pembroke Street è vuota, e così pure

Leeson Street. Questo è il tempo dopo il tempo,

l’aspetto che avrà il mondo quando il mondo

sarà finito, quando la gente sarà stata accompagnata

ai posti loro riservati nei paradisi

luminosi.

Verso l’angolo tra

Upper Pembroke Street e Leeson Street

c’è un anziano signore che indossa una mascherina;

il passo è svelto, i movimenti vivaci. Ne colgo

lo sguardo lacrimoso per un attimo lacrimoso.

Senza fermarsi, come fosse un dato di fatto,

dice: “Mi avevano detto che lei era morto”.

*

Vinegar Hill

The town reservoir on the hill

Was built in the forties.

If you lifted a round metal covering

And dropped a stone, you could

Hear it plonk into the depths.

There were small hollows in the rocks

That, no matter how dry the weather,

Were filled with rainwater.

These rock-pools must have been here

With different water in them

That summer when the rebels

Fled towards Needham’s Gap.

From the hill, as the croppies did,

You can view the town, narrow

Streets even narrower, and more

Trees and gardens than you imagined.

It was burning then, of course,

But now, it is quiet. There is,

In the Market Square, a monument

To Father Murphy and the Croppy Boy.

We can see the hill from our house.

It is solid rock in the mornings

As the sun appears from just behind it.

It changes as the day does.

My mother is taking art classes

And, thinking it natural to make

The hill her focal point,

Is trying to paint it.

What colour is Vinegar Hill?

How does it rise above the town?

It is humped as much as round.

There is no point in invoking

History. The hill is above all that,

Intractable, unknowable, serene.

It is in shade, then in light,

And often caught between

When the blue becomes grey

And fades more, the green glistens,

And then not so much. The rock also

Glints in the afternoon light

That dwindles, making the glint disappear.

Then there is the small matter of clouds

That make tracks over the hill in a smoke

Of white as though instructed

By their superiors to break camp.

They change their shape, crouch down

Stay still, all camouflage, dreamy,

Lost, with no strategy to speak of,

Yet resigned to the inevitable:

When the wind comes for them, they will retreat.

Until this time, they are surrounded by sky

And can, as yet, envisage no way out.

Vinegar Hill

Il serbatoio della città, sulla collina,

è stato costruito negli anni Quaranta.

Se sollevavi il coperchio rotondo di metallo

e buttavi un sasso, ne sentivi

il tonfo giù in profondità.

C’erano delle piccole cavità nelle rocce

che, per quanto asciutto fosse il tempo,

si riempivano di acqua piovana.

Queste pozze devono esserci state

con dentro un’acqua diversa

l’estate che i ribelli fuggirono

verso Needham’s Gap.

Dalla collina si vede la città,

come fecero i croppies,*

stradine ancora più strette, e più

alberi e giardini di quanto si immagini.

Era in fiamme allora, ovviamente,

ma ora è tranquilla. C’è,

in Market Square, un monumento

a Padre Murphy e il Croppy Boy.

Da casa nostra si vede la collina.

La mattina, quando da dietro

spunta il sole, è solida roccia.

Cambia col cambiare del giorno.

Mia madre sta seguendo lezioni di pittura

e, trovando naturale fare della collina

il suo punto di riferimento,

sta cercando di dipingerla.

Di che colore è Vinegar Hill?

Come si alza al di sopra della città?

È rotonda, con una gobba.

Non ha senso invocare

la Storia. La collina è altro,

intrattabile, impenetrabile, serena.

È in ombra, poi in luce,

e spesso colta fra le due

quando l’azzurro diventa grigio

e sfuma ancora di più, il verde luccica,

e poi non così tanto. Anche la roccia

brilla nella luce pomeridiana

che cala e le toglie il lucore.

E poi c’è quel piccolo gruppo di nubi

che se ne vanno sopra la collina

in un fumo bianco come fossero istruite

dai loro superiori a levare il campo.

Cambiano forma, si rannicchiano,

restano immobili, si mimetizzano, sognanti,

smarrite, senza una vera strategia,

eppure rassegnate all’inevitabile:

prese di mira dal vento, si ritirano.

Fino ad allora, sono circondate dal cielo

e ancora non prevedono una via d’uscita.

*

Dead Cinemas

I.

Dublin is a map

Of dead cinemas, once

Darkened spaces now

Demolished, made into

Shops or just closed up.

The Grafton, where I saw

‘Love in the Afternoon’,

And wondered if Bernard

Verley was right not to do

What he did not do.

The Astor, where one Friday

At the early evening show

I saw ‘Cries and Whispers’

And screamed out loud

When she cut herself.

The Academy in Pearse Street,

Where I saw ‘Amarcord’,

Or most of it, since

The censor scissored out

The whole wanking scene.

The world is divided:

Men and women; black and white;

Rich and poor; and those who

Go to the cinema alone

And those who do not.

In the Regent, on my own,

I saw ‘The Deerhunter’

And ‘Halloween 11’. It was

A bad period made worse

By going to those two films.

The International had the grace

To become the IFC,

Where I saw ‘The Stepford Wives’

And ‘Salò’. It eventually became

The Sugar Club.

In the Green Cinema, I saw

‘The Great Gatsby’, with

Robert Redford and Mia Farrow

But did not believe a single

Shot in the whole fiasco.

In the Screen opposite Trinity

Over a whole weekend

In the company of Mary Holland

I saw all of ‘Heimat’; it started

Good, then fell apart slightly.

In Abbey Street, below

The Adelphi, there was

A small cinema where late

One Sunday night

In the winter of 1975

I saw Polanski’s ‘Repulsion’

Which was not as frightening

As the walk back home to

Hatch Street, with Dublin

Damp, emptied out.

Soon, there were art films

And other films; the former

Did not have ads for

McDowell’s Happy Ring House

And were more solemn generally.

In the end I stopped

Going much because

I found it hard

Facing back out

Into the world.

Cinema defunti

I.

Dublino è una mappa

di cinema defunti, un tempo

spazi oscurati, ora demoliti,

trasformati in negozi o

semplicemente chiusi.

Il Grafton dove ho visto

L’amore il pomeriggio

e mi sono chiesto se Bernard

Verney avesse fatto bene a non fare

ciò che non aveva fatto.

L’Astor, dove un venerdì

al primo spettacolo serale

ho visto Sussurri e grida

e ho gridato io a voce alta

quando lei si è tagliata.

L’Accademia di Pearse Street,

dove ho visto Amacord,

o la maggior parte, dato che

la censura aveva amputato

l’intera scena delle seghe.

Il mondo è diviso:

uomini e donne, bianchi e neri;

ricchi e poveri;

chi va al cinema da solo

e chi non lo fa.

Nel Regent ho guardato,

da solo, Il cacciatore

e Il signore della morte. Era

un brutto periodo, peggiorato

dall’aver visto quei due film.

L’International si è potenziato

in “Istituto cinematografico”,

dove ho visto La fabbrica delle mogli

e Salò. Alle fine sarebbe diventato

The Sugar Club.

Al Green Cinema, ho visto

Il grande Gatsby

con Robert Redford e Mia Farrow

ma non ho creduto una singola

ripresa dell’intero fiasco.

Nello Screen davanti a Trinity

per un intero fine settimana

abbiamo guardato, io e Mary Holland,

l’intero Heimat; è partito bene

ma poi ha un po’ perso il filo.

In Abbey Street, dopo

L’Adelphi, c’era un piccolo

teatro dove,

una domenica sera sul tardi

nell’inverno del 1975,

ho visto Repulsione di Polanski

che è stato meno spaventoso

della camminata di ritorno a casa mia

in Hatch Street, in una Dublino

umida e svuotata.

Presto ci furono film d’autore

e film di altro genere; ai primi

mancavano le pubblicità per

McDowell’s Happy Ring House

ed erano complessivamente più solenni.

Alla lunga ho smesso

di andare più di tanto, perché

trovavo difficile

girarmi poi di nuovo

verso il mondo.